I love research! That’s why I’ve dedicated most of my career to clinical research—studies that are done on people—to better understand the human breast and, ultimately, gain new insights into what causes breast cancer.

To some, it might sound boring to study the same thing year after year, decade after decade. But it’s actually a continual adventure. You make observations about how a disease develops and grows, using the tools that are available at the time. Then you make a hypothesis and test it. Sometimes it is right; often it is not. Either result gives insights into how to take the next step forward.

Many of you know that back when I started as a breast surgeon, the thinking was that we had to move as quickly as possible and do as big a surgery as possible to prevent the cancer from spreading to the rest of the body. We would do a biopsy under general anesthesia and it would be read immediately by the pathologist while we waited with the patient asleep. If it was cancer, we proceeded with a radical mastectomy. Many women went to sleep not knowing whether they would wake up without a breast! Thanks to clinical research and courageous women willing to be randomized in a clinical trial comparing mastectomy to a lumpectomy and radiation, we learned that removing the breast did not improve survival.

Since then we have learned that more often than not microscopic cancer cells can be found in the blood early on in the tumor’s development, and that the speed and extent of the surgery is not the key factor in survival. This new information has also pushed us to reevaluate whether annual screening is as important as we once thought it was. As my professor once told me, “If we knew what we were doing we wouldn’t call it research.”

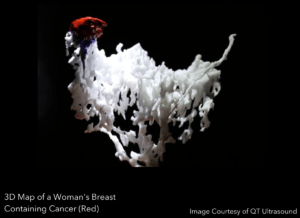

We have recently made some key discoveries in our own research—and I couldn’t be more excited by how what we are learning is expanding my understanding of the breast. We now have the first 3D printing of the anatomy of the human breast!

These images were obtained using QT ultrasound technology and through our partnership with the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, we are now studying a collection of these images to identify both usual patterns of ducts inside the breast and common variants. My hope is that we will one day be able to apply this technology clinically. Imagine this: Everybody has a map of their own ductal systems, that can be monitored for changes.

This would allow us to think about new ways to use ductoscopy—inserting a tiny scope through the nipple to explore a duct. We could then collect fluid from the duct that has developed some changes. This would be a single-duct liquid biopsy that would tell us what’s going on inside the duct and help us decide what treatment to put directly into the duct to get rid of any cells that are starting to go awry.

While we are exploring the ducts, we can revisit our breast microbiome study. The original human microbiome project ignored the breast. But studies done since then have described all the bacteria and viruses the breast contains. The problem, however, is that these studies all looked as the breast as a whole. They didn’t look for bacteria and viruses in the duct or the fluid inside of it.

I have wanted to do that for years. Recently, I was asked by a research team formed from a company (Atossa) and clinicians at Johns Hopkins to help them with a research study that will study the effects that hormone therapy has on cancer cells when it is put inside the breast ducts prior to surgery. I was happy to help—as long as I could also collect a fluid sample from the breast ducts to study their microbiomes. They thought that was a great idea. Stay tuned and we may well be able to see if the microbiome of the duct with cancer is different than that in other ducts!

The lesson is to never give up. Research means looking again and again at a problem from every angle and taking advantage of every opportunity that comes your way! Stay tuned as we (re)search the human breast!