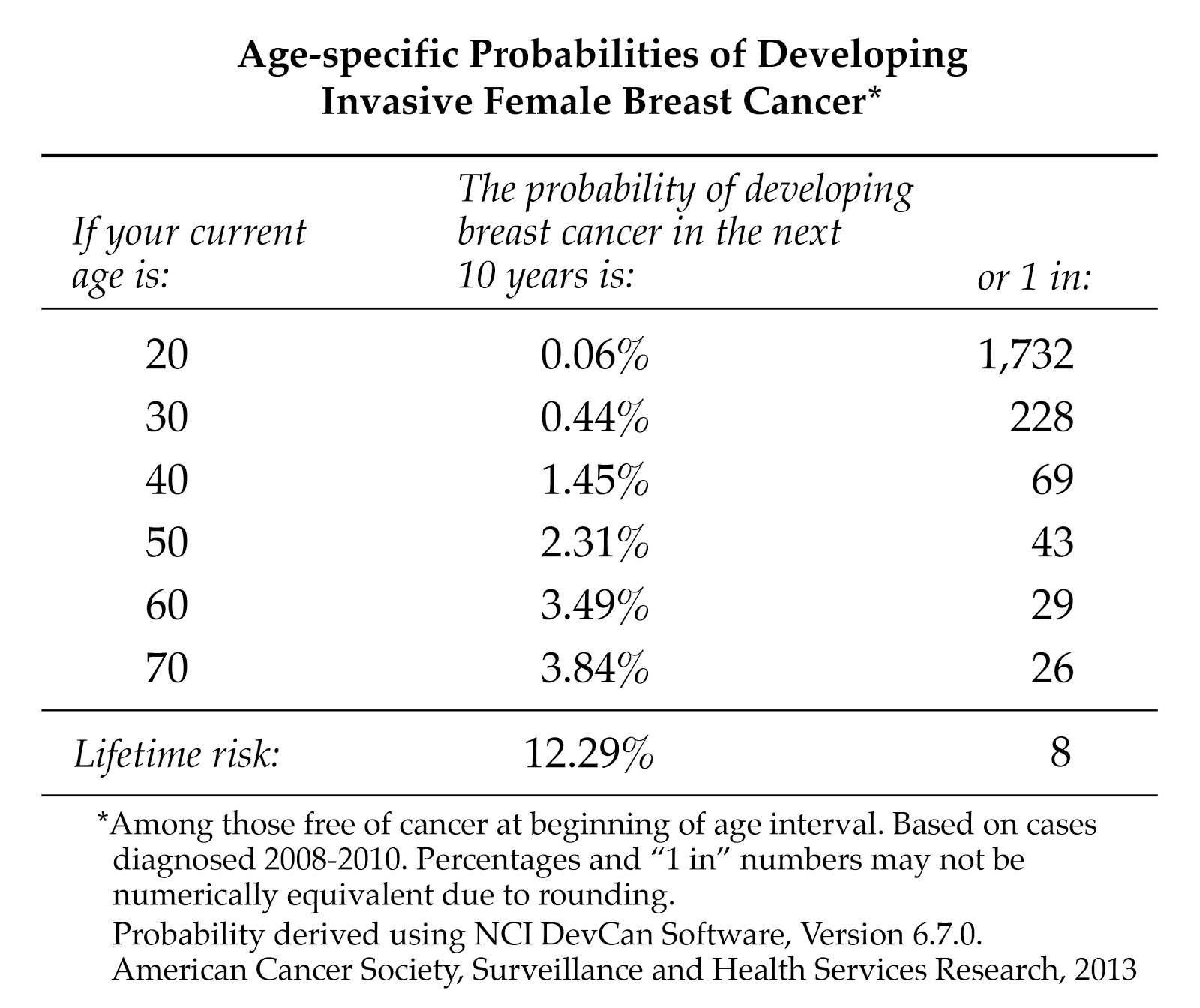

A woman living in the U.S. has a 12.3%—or one in eight—chance of being diagnosed with breast cancer in her lifetime.

Risk factors are biological, environmental, and lifestyle traits, habits, or exposures that make some people more susceptible than others to a particular disease. These risk factors increase risk over time to 12.3%.

Studies have identified some factors that increase breast cancer risk. But these risk factors only explain a small piece of the breast cancer puzzle. Studies show that about 70% of the women who develop breast cancer have no risk factors in their background.

Known Breast Cancer Risk Factors

- Gender—Breast cancer is 100 times more common in women than men.

- Age—A person’s risk of cancer increases with age. Most breast cancer—about 79% of new cases and 88% of breast cancer deaths occur in women 50 years of age and older.

- Race—White women are slightly more likely to develop breast cancer than are African American women, but African American women are more likely to die of the disease. Asian, Latina, and Native American women have a lower risk than white women of developing breast cancer. This disparity may be due, in part, to access to cancer screening.

- Family history—About 30% of women who develop breast cancer have a family history of the disease.

- Reproductive factors—The younger a woman is when she gets her first period and the older she is when she goes into menopause, the more likely she is to get breast cancer.

- Pregnancy—Women who have never been pregnant are at higher risk than are women who have a child before 30. However, women who have their first pregnancy after 30 have a higher risk than those who have never been pregnant.

- Radiation exposure—Radiation is a known risk factor for cancer in general. Several major studies have confirmed the link between radiation and increased risk of breast cancer.

- Previous abnormal breast biopsy—If a biopsy indicates that a woman has atypical hyperplasia, she has about a four times greater risk of developing breast cancer. What does this mean? Among a typical group of 100 women, five of them would be expected to develop breast cancer. Among a group of 100 women with atypical hyperplasia, 19 of them would be expected to develop breast cancer.

- Diethylstilbestrol (DES)—In the 1940s through the 1960s, doctors gave some pregnant women DES because it was thought to reduce the risk of miscarriage. These women have a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer.

- Hormone replacement therapy (HRT)—Long-term use (several years or more) of HRT slightly increases breast cancer risk.

- Alcohol—Studies indicate that drinking alcohol slightly increases risk.

- Obesity—Studies indicate being overweight increases breast cancer risk, especially for postmenopausal women. This is because fat tissue increases estrogen levels and high estrogen levels increase breast cancer risk.

- Physical activity—Studies suggest that exercise reduces both breast cancer risk and the risk of a cancer recurrence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Will using birth control pills increase my risk of getting breast cancer?

When the birth control pill arrived on the market, no one was certain of the long-term effect it might have on a woman's health. This question took on increased importance as an association between hormones, estrogen in particular, and breast cancer risk became more apparent.

A meta-analysis—a study that analyzes the results of many previous studies—published in September 1996 put many fears to rest. This analysis of 50 previous studies found that women taking the pill had only a 1.24% greater chance of developing breast cancer than women who did not take the pill.

For women with a family history of breast cancer, the risk is a bit higher, according to a study published in 2000 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. However, this study was looking at women who took birth control pills that had higher levels of hormones than the pills used today. Moreover, all family histories are not the same.

A woman whose mother was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 40 is more likely to carry a genetic mutation that increases cancer than is a woman whose mother was diagnosed at age 65. Also, the pill offers benefits that may outweigh the risk. For example, women who take the pill for five or more years have a decreased risk of developing ovarian cancer, even if they have a BRCA mutation.

The bottom line: If you have a family history of breast cancer, discuss your individual risk with your doctor and then decide if the pill is right for you. But remember, the pill only protects against pregnancy. It does not protect against sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV. For that, you need to use condoms.

More Information:

- Oral Contraceptives and Cancer Risk Fact Sheet National Cancer Institute

- The Birth Control Pill and Breast Cancer Risk WebMD

Do women who take antidepressants have an increased breast cancer risk?

Depression is a serious medical illness, and one that should never be ignored. For some women, depression is situational and goes away in time. For others, depression may be more a part of how they are wired, and it may be something that is a constant part of their lives.

Some people find that antidepressants are what it takes to help them with their depression. Others have found that psychotherapy is more effective. And still others have found that it is the combination of the two that works best for them.

Since the 1970’s researchers have been studying the relationship between antidepressant use and breast cancer risk. One of the most recent studies was a meta-analysis of 18 previous studies, published in Breast Cancer Research & Treatment in December 2012. This analysis did not find a “clinically meaningful association” between the use of antidepressants and breast cancer, which researchers said, “should provide considerable reassurance,” to a woman who is taking an antidepressant to take care of her mental health needs.

Will drinking alcohol increase my risk of getting breast cancer?

Hundreds of studies have looked at whether women and men who drink alcohol have an increased risk of developing cancer. Many of these studies have focused on whether drinking alcohol increases a woman’s risk of breast cancer. In 2002, researchers published a meta-analysis (a study that analyzes data from previous studies) of the data collected from 53 studies looking at alcohol, tobacco, and breast cancer risk.

The meta-analysis included 58,515 women with breast cancer and 95,067 healthy women. It found that women who drank between 1.2 and 1.5 ounces of alcohol a day had a slightly higher risk of developing breast cancer than women who did not drink at all. The risk was a bit higher in women who reported drinking 1.6 ounces or more of alcohol per day. The researchers concluded that, if these observed relationships were actually causal, about four percent of the breast cancers in developed countries are attributable to alcohol. They also noted that drinking alcohol is more closely associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis and cancers of the esophagus, mouth, larynx, and liver.

Some studies suggest a diet high in folic acid—found in spinach, broccoli, corn, legumes, and multivitamins—appears to mitigate the risk of alcohol. So if you enjoy a daily cocktail or glass of wine, you may want to increase your green leafy vegetables and take a multivitamin. The recommended daily dose of folate is 400 micrograms. The maximum safe daily dose is 1,000 micrograms.

Whether or not to stop drinking to reduce breast cancer risk is one of the many decisions we each must make. The breast-cancer risk increase isn't great, but it definitely exists. You alone know how much pleasure you get from your glass of wine or beer, and how alarmed you are at the thought of breast cancer. If it's not all that important to you to drink, you might want to reduce your alcohol consumption to a glass of champagne on major celebrations.

I am transgender. What is my risk of getting breast cancer?

The bottom-line up front: We don't know. That's because we have no data on the incidence of breast cancer in transsexual or transgendered individuals. There are, however, some things we have learned about risk from non-trans women that could impact breast cancer risk in trans individuals.

Male-to-Female (MTF) Individuals

In non-trans women, breast cancer risk is related to hormone exposure. This means we can probably assume that MTFs who have used hormones (estrogen and/or progestin) for five years or more may have a higher risk than non-trans men. MTFs also may be at greater risk if they started taking these hormones at a young age.

There is no evidence that breast implants increase breast cancer risk in MTFs or in non-trans women. However, implants do make it harder to see cancer on a mammogram.

Female-to-Male (FTM) Individuals

FTMs who have used testosterone, which the body converts to estrogen, may be at higher risk than the average non-trans man of developing breast cancer. Because of breast tissue that remains in the chest wall after surgery, this is true even for FTMs who have had surgery. (It's the same reason why non-trans women who have had a prophylactic mastectomy still have a small risk of developing a breast cancer.)

Breast Cancer Screening

- MTFs should begin having an annual chest/breast exam and mammography screening at age 50.

- FTMs who have not had chest surgery should begin having mammography at age 50.

Other things to consider:

In trans and non-trans people alike, there are other factors, like family history, that influence breast cancer risk. So, be sure to tell your doctor if you have any family members who have had breast cancer. Also, it's important you be open and honest about your current or past hormone use, even if you had obtained these hormones in unconventional ways.

More Information:

- Transgender People and Cancer National LGBT Cancer Network

- Breast Cancer in Transgender Veterans: A 10-Case Series LGBT Health

- Breast Imaging in the Transgender Patient American Journal of Roetgenology

Will eating soy increase my risk of getting breast cancer?

You can find information circulating online that says eating soy will increase your risk of getting breast cancer. That’s because in the mid-1980’s as scientists began to study why soy was good for your health, they discovered when they added genistein, which is a type of isoflavone, to breast cancer cells in a laboratory dish, the cells grew faster. Soon after, it was suggested women who were taking tamoxifen and other anti-estrogens should avoid soy because soy acted like a weak estrogen, and could potentially counteract the tamoxifen or increase a woman's risk of recurrence.

Then, in December 2009, researchers published findings from the Shanghai Breast Cancer Survival Study that changed our opinion of soy yet again. In this study of 5,024 breast cancer survivors, the women who ate the most soy protein or soy isoflavones were the least likely to have a recurrence or die from breast cancer. This was true regardless of whether their tumor was ER-positive or ER-negative; whether or not they were taking tamoxifen; and whether they were pre- or postmenopausal. (While the researchers didn't look at this question, the findings would be expected to be the same for women on an aromatase inhibitor.)

The study's authors pointed out that women in Asia tend to eat different types of soy than women in the U.S. In Asia, women are more likely to eat whole soy foods, like cooked soybeans, edamame, tofu, miso, and soy milk. In the U.S., women tend to eat more processed foods that contain soy—and at much lower levels. This means women in the U.S. might not be seeing the same benefits from soy as women in Asia do. It is not recommended that women use soy powders or supplements. Real food is best.

What about soy lecithin, which is found in many foods? It is extracted from soybeans, but it is not part of the soy protein. As a result, it does not contain any isoflavones, which are the part of the soybean that acts as an estrogen. It is primarily used as an emulsifier to hold ingredients together. So, there is also no reason to worry you are getting a lot of isoflavones in your diet each time you chew gum.

Does having had an abortion increase my risk of getting breast cancer?

Two large studies, the first published in 2004 and the second published in 2008, found having an abortion or a miscarriage does not increase a woman's risk of developing breast cancer, nor does the number of abortions.

The findings from these large international studies are important for two reasons. One, they should reassure women that having an abortion does not increase their breast cancer risk. Two, they loudly dispute the lobbying and public relations efforts of groups like the Coalition for Abortion/Breast Cancer Risk that use results from poorly designed retrospective studies to increase fears about abortion and breast cancer. These groups also have been able to get a number of states to pass legislation requiring doctors to inform women that abortion may increase their breast cancer risk.

In 2003, the National Cancer Institute held a workshop on Early Reproductive Events and Breast Cancer, where breast cancer experts who reviewed all the published literature, concluded there was no link between abortion and breast cancer. The group went on to publish a report on their findings.

It should now be clear that abortion does not increase breast cancer risk. Anyone who continues to make that claim is dangerous, irresponsible, and ignoring the evidence.

I have lumpy breasts. Does that increase my risk of getting breast cancer?

Researchers estimate one in five women who have a mammogram over the next 10 years will require a biopsy to further investigate a suspicious lump. Waiting for these biopsy results can be agonizing, Yet most of the time women are told they have benign breast disease, not cancer.

A study published in 2005 in the New England Journal of Medicine confirmed most women with benign breast lumps have only a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer over the next 15 years. This study followed 9,087 women who had been diagnosed with benign breast disease. After 15 years, 707 (less than .08%) of these women had developed breast cancer.

The researchers found breast cancer risk was linked to the type of benign breast disease a woman had. In a group of 100 women without benign breast disease, five would be expected to develop breast cancer. In the study:

- Two-thirds of the women had cysts that contained normal-looking cells, a condition called nonproliferative disease. These women were 27% more likely to develop breast cancer. In a group of 100 women with nonproliferative disease, six would go on to develop breast cancer.

- Thirty percent had cysts that contained a large number of normal cells, a condition called proliferative disease. These women were 88% more likely to develop breast cancer. In a group of 100 women with proliferative disease, 10 would be expected to get breast cancer.

- Four percent had atypical hyperplasia. These women were 324% more likely to develop breast cancer. In a group of 100 women with atypical hyperplasia, 19 would be expected to be diagnosed with breast cancer.

This study, like previous studies, found breast cancer did not always develop in the same breast with the benign breast disease. Of the 616 women who developed breast cancer in one breast, 342 (55.5%) developed breast cancer in the breast that was biopsied while 274 (44.5%) developed breast cancer in the other breast.

Dr. Love says: Benign breast disease, also sometimes referred to as fibrocystic breast disease, is very common. The National Cancer Institute estimates that as many as 60% of premenopausal women will have benign breast disease at some point in their lives. However, there is only one type of benign breast disease that is of concern—atypical hyperplasia.

If you are diagnosed with benign breast disease after a biopsy, you should find out what the pathologist saw under the microscope so you can fully understand what the findings mean.

If your biopsy shows you have atypical hyperplasia, you shouldn’t panic. It does not mean you will develop breast cancer. In fact, most women who have atypical hyperplasia do not develop breast cancer. But you are at higher risk. For that reason, you will want to make sure you undergo regular mammography screening.

You may also want to discuss with your physician the risks and benefits of taking tamoxifen for breast cancer risk reduction.

Do women who smoke have a greater risk of getting breast cancer?

We've known for decades that tobacco increases the risk of lung cancer, as well as cancers of the mouth, lips, nose, throat, larynx, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, kidney, bladder, uterus, cervix, and colon. A growing body of evidence suggest breast cancer should be added to that list as well, with the most recent studies suggesting that women who start smoking at an early age have the greatest increased risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer, especially if they started smoking prior to giving birth. The risk may possibly be higher in women who become heavy smokers at a young age. And there’s science to support the connection. The International Agency for Research on Cancer has identified 20 known or suspected substances in tobacco smoke that can increase breast cancer risk, as well as biological mechanisms that explain how exposure to these carcinogens could lead to breast cancer.

Studies on secondhand smoke have had consistent findings. These studies found younger, premenopausal women who have never smoked but did have exposure to secondhand smoke have an increased breast cancer risk. Whether secondhand smoke is also linked to postmenopausal breast cancer is not yet clear.

In addition, studies have found women who smoke are at increased risk of having a breast cancer recurrence.

If you or someone you know smokes, it's never too late to quit. SmokeFree.gov offers tips and support for quitting. And if you don't smoke, spend as much time as you can in smoke-free environments. It will do a lot for your lungs–and it could decrease your risk of breast cancer too!

What are the links between the environment and breast cancer?

We now believe cancer is probably caused by a combination of genes that are mutated by carcinogens and find themselves in an environment conducive to growth and spread.

Genes don't exist in isolation; they interact with the environment, which can contain carcinogens—molecules that cause additional DNA mutations. Even though we may be born with a mutation, other factors that exert their effects later may be necessary to trigger cancer. If we could figure out what these are and block the key environmental factors, it would matter less which genes have mutations. In terms of breast cancer we are studying diet, alcohol consumption, hormone medications, and pesticides to determine which are carcinogenic.

Sources of estrogen in the environment are organochlorines (DDT) and PCBs, persistent environmental contaminants known as estrogen mimics that have been identified throughout the global ecosystem in, for example, fish, wildlife, and human tissue, including blood and breast milk. One reason many people believe DDT and PCBs are related to breast cancer is that a lot of them are broken down in the body to weak forms of estrogen, which, it's thought, can stimulate and cause breast cancer just as estrogen can.

Phytoestrogens like soy and the weak estrogen tamoxifen have very different effects. The biology of estrogen, estrogen receptors, and the selective estrogen receptor modulators is very complex. That’s why making connections between sources of estrogen and cancer risk must take into consideration time of exposure and other associated risk factors.

In 2010, the President's Cancer Panel released the report, "Reducing Environmental Cancer Risk: What We Can Do Now". This report provides an excellent overview of what is currently known about environmental cancer risks and the type of research that needs to be done for us to learn more.

There are a number of organizations that focus attention on environmental cancer risk factors. These include:

-

Breast Cancer Action A national grassroots education and advocacy organization located in San Francisco, California.

-

Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Program A transdisciplinary study of of the effect of environmental exposures on mammary development and potential breast cancer risk.

-

California Breast Cancer Research Program A research program that aims to prevent and eliminate breast cancer through research, communication and collaboration in the California region.

-

Massachusetts Breast Cancer Coalition A nonprofit organization dedicated to preventing environmental causes of breast cancer through community education, research advocacy, and changes to public policy.

- Silent Spring Institute A nonprofit scientific research organization dedicated to identifying the links between environment and women's health, especially breast cancer.

Another good resource is the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, which released a report on Breast Cancer Risk and Environmental Factors.

My mother took DES. What is my risk of getting breast cancer?

DES (diethylstilbestrol) was used between the 1940s and 1960s to increase fertility and prevent miscarriage. Not only was it ineffective, but it had health consequences for the women who used it, and for their children.

A study in 1984 showed a slight increase—1.4%—in breast cancer among women who took DES while pregnant. The reasons for this are not clear, as estrogen levels are already high during pregnancy. But it has been postulated the breast is more sensitive to estrogen during pregnancy.

Studies have shown the daughters of women who took DES are at increased risk of developing cancer of the vagina or cervix. DES daughters may also have a slightly higher risk of developing breast cancer after age 40. A study published in October 2011 in the New England Journal of Medicine that compared 4,600 women who had been exposed to DES in utero with 1,900 women who had not, found in women 40 years of age or older the cumulative breast cancer risk was 3.9% for those who had been exposed compared with 2.2% for those who had not—making the risk about 2% higher in the DES daughters.

More Information:

- DES Action A resource for DES-exposed mothers, daughters, and sons who may need special health care.

- NIH—DES: Questions and Answers Answers common questions about DES.

- DES Cancer Network A resource for DES-exposed women and their families.

- CDC DES Update Campaign Provides information about DES exposure.

Do X-rays increase breast cancer risk?

Radiation is a known risk factor for cancer, and at least three major studies have confirmed a link between radiation and an increased risk of breast cancer. These studies indicate the danger is from exposure to moderate doses of radiation (10-500 rads), and the danger is only to the area of the body at which the radiation has been aimed.

This exposure differs from the kind you get with diagnostic chest X-rays and mammograms. Many people are legitimately concerned about such X-rays, but it's a mistake to throw out a highly useful diagnostic tool. Remember that the danger comes with a total cumulative dose of radiation. If you had a chest X-ray every week for two years, you probably would increase your risk of getting breast cancer. But the danger of leaving pneumonia undetected, if you have reason to believe it may exist, is far greater than any danger from infrequent chest X-rays. Similarly, the level of radiation in up-to-date mammograms (1/4 of a rad) won't increase your risk of breast cancer, except if you carry a very rare gene that makes you more sensitive to radiation.

Can exposure to electromagnetic fields increase my breast cancer risk?

Electric and magnetic fields (EMFs) arise from the motion of electric charges. They are characterized as nonionizing radiation when they lack sufficient energy to remove electrons from atoms, as opposed to ionizing radiation such as X-rays and gamma rays.

EMFs are emitted from devices that produce, transmit, or use electric power such as power lines, transmitters, and common household items like electric clocks, shavers, blankets, computers, televisions, and microwave ovens.

Several studies published in 2003 explored the connection between electric blankets and breast cancer. These studies found no connection between electric blanket use and breast cancer risk. A study published in 2004 found a slight increased risk in women exposed to EMFs at work or at home. Since then, there has been little published research on EMFs and breast cancer and, to date, scientists have not identified how EMFs could cause cancer.

You can learn more about EMFs and cancer here.