Is it true that adolescent girls can develop breast cancer? I just read an article about a 14-year-old girl who was said to have the disease.

While in rare instances a teenage girl may have to have surgery to remove a lump from her breast, it is virtually unheard of for that lump to be breast cancer. The lumps that these girls have are not the type of tumor that becomes breast cancer but are either juvenile fibroadenoma or cystosarcoma phyllodes.

Fibroadenoma is the second most common form of benign breast disease; it is most common in women under 30. Juvenile fibroadenoma is a benign growth that occurs when normal breast development goes slightly awry. Fibroadenomas are hard, round, and easy to feel. And although they can be very large—as big as 8–9cm—they are unlikely to cause any pain.

Fibroadenomas are removed because of their size, not because they are cancerous or because they will become cancerous. And while it is certainly scary for a teenage girl to have to think about having surgery on her breast, it is important that she and those who support her understand that she has a lump, not cancer.

Cystosarcoma phyllodes is a tumor that occurs only in the breast, and what causes it remains unknown. It is very rare—less than one percent of all breast tumors are classified as cystosarcoma phyllodes.

Even though cystosarcoma phyllodes contains the word sarcoma (which would make you think of cancer), the majority of these tumors are benign. This is why doctors have begun to refer to them as phyllodes tumors.

Phyllodes tumors tend to be large—the average size is about 5cm—and to grow very quickly. Like a fibroadenoma, these tumors do not typically cause any pain and are hard, round, and easy to feel.

Phyllodes tumors are typically removed with an excision. If the tumor recurs, which happens about 20–35 percent of the time, a second excision or possibly a mastectomy may be needed.

About 10% of phyllodes tumors metastasize, and when they do they typically spread to the lung, bones, heart, and liver. Unlike with a typical breast tumor, there is no systemic treatment (chemotherapy or hormonal therapy, like tamoxifen) that phyllodes tumors have been found to respond to. They do not respond to radiation either. It is important to keep in mind, though, that these tumors are rare to begin with, and even rarer in teenage girls

I was diagnosed with Juvenile Papillomatosis (Swiss cheese disease) at the age of 18. I am now 25. Can you tell me more about this breast disease?

Juvenile Papillomatosis is a rare benign breast condition associated with fibrocystic changes. It is typically first diagnosed in late adolescence.

Juvenile Papillomatosis typically occurs in females, but a few cases have been reported in males, too. It is estimated that about one-third of the cases of Juvenile Papillomatosis develop in individuals who have a family history of breast cancer.

Because Juvenile Papillomatosis is considered a precancer, it is recommended that adolescents who are diagnosed with this form of breast disease be seen annually by a breast specialist at a breast care center that treats women and men who are at high risk for developing the disease.

Both my mother and aunt developed breast cancer when they were postmenopausal. I had genetic testing and learned that I don't carry one of the BRCA gene mutations. But I'm still worried that I, too, might get breast cancer. Should I take tamoxifen or raloxifene to reduce my risk?

In families where women are genetically predisposed to getting breast cancer because of an inherited gene, we typically find that there are several family members who had premenopausal, bilateral breast cancer and/or ovarian cancer. Because your mother and aunt were both postmenopausal when they were diagnosed, it is less likely that their breast cancer is related to a genetic predisposition.

Still, it makes sense that you would be thinking about taking tamoxifen. The data we have on the use of tamoxifen for risk reduction comes from the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial. This study enrolled women who were at high risk for developing breast cancer because they had a family history of breast cancer or had been diagnosed previously with atypical hyperplasia or lobular carcinoma in situ. Half of the women were given tamoxifen for five years; the other half were given a placebo.

The results from this trial were first presented in 1998. Final results were published in 2005. At that time, after seven years of follow-up, researchers found that 145 cases of invasive breast cancer had developed among the women taking tamoxifen compared to 250 cases in the women who had been given a placebo. In a group of more than 13,000 women, those aren't very large figures. Tamoxifen was also found to reduce a woman's risk of developing atypical hyperplasia.

The Breast Cancer Prevention Trial found that there were clear risks from taking tamoxifen. Women taking tamoxifen were at increased risk for cardiovascular disease, stroke, gallbladder disease, blood clots in the legs, cataracts, and uterine cancer. These may be risks worth taking to cure cancer, but we need to determine whether risk is warranted in the prevention setting. In the prevention trial some women died from a pulmonary embolism they got trying to prevent a cancer they might never have developed in the first place.

Another option is the drug raloxifene (brand name Evista) which was approved for use as breast cancer prevention for postmenopausal women in September 2007 (In contrast, tamoxifen can be used by both pre- and postmenopausal high-risk women for breast cancer prevention). This approval was the result of the findings from the STAR trial, which compared raloxifene to tamoxifen. The STAR trial found raloxifene and tamoxifen were basically equivalent in terms of their ability to prevent invasive cancer, with both drugs reducing a woman's risk by about 50%. It is important to note that we do not have any data that show a survival benefit from taking tamoxifen or raloxifene, only a benefit in reducing the risk of the development of disease.

Additionally—and unexpectedly—STAR found that tamoxifen was more effective than raloxifene in reducing the incidence of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), which are precursors to invasive breast cancer. Specifically, the study found that 57 of the women in the tamoxifen group developed DCIS or LCIS compared with 81 in the raloxifene group. Why raloxifene would reduce the risk of invasive breast cancer but not DCIS or LCIS isn't clear. It's also important to note that these drugs only reduce a woman's risk of getting a tumor that is ER-positive. They do not reduce the risk of ER-negative breast cancers.

Another option you may want to consider is ductal lavage. Ductal lavage is a washing procedure that can identify cancerous and precancerous cells in the milk ducts of the breast. It is currently approved for use in women who are at high risk for developing breast cancer. The information you gain from the ductal lavage procedure may help you determine if taking tamoxifen or raloxifene is a good option for you right now.

I am high risk and have decided that I want to take hormone therapy to reduce that risk. How do I decide between tamoxifen and raloxifene?

This is a question more women are asking now that raloxifene has been approved for breast cancer prevention.

The first thing to consider is whether you are pre- or postmenopausal. Tamoxifen can be used by both pre- and postmenopausal women. Raloxifene, however, is only approved for use in postmenopausal women as it has not been tested in premenopausal women.

The STAR trial, which was what led to raloxifene's FDA approval for use in the breast cancer prevention setting, found that raloxifene and tamoxifen were equally effective in reducing a high-risk postmenopausal woman's chances of developing invasive breast cancer. However, tamoxifen was slightly better than raloxifene in preventing the development of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), which is a precursor to breast cancer, and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), which is a marker of increased breast cancer risk. Specifically, the STAR trial found that among the 9,726 women in the tamoxifen group, 57 developed LCIS or DCIS, compared to 81 of 9,745 women in the raloxifene group. Why raloxifene would reduce the risk of invasive breast cancer but not LCIS or DCIS isn't clear, but it does tell us the two drugs work in slightly different ways.

The two drugs have similar side effect profiles. STAR found that a woman's risk of developing blood clots, stroke, or uterine cancer appeared to be about the same for both drugs. Tamoxifen is known to double a woman's risk of developing uterine cancer to a rate of about 2 cases per 1,000 women per year. The STAR trial found that 36 of the 9726 women taking tamoxifen developed uterine cancer and 141 developed blood clots compared with 23 cases of uterine cancer and 100 incidents of blood clots in the 9745 women taking raloxifene. (Although the number was lower in the raloxifene group, the difference was not statistically significant, which means it could have happened by chance.)

The STAR trial also found that women who took tamoxifen were more likely to experience hot flashes, vaginal bleeding, bladder control problems, and leg cramps, but that women taking raloxifene were more likely to experience pain during sexual intercourse and joint pain.

So, it's pretty much of a tossup. I would encourage you to talk with your physician about your current health and which side effects you are most concerned about. Perhaps the best way to look at it is that now that there are two options you can try one and, if the side effects are too much, try the other, knowing that either drug will be equally effective in reducing your risk of invasive breast cancer.

My father recently died from male breast cancer. His father had breast cancer and he has a sister who has breast cancer. What are my chances of getting breast cancer?

Families with a lot of male breast cancer usually carry the BRCA2 gene. This is one of the two breast cancer genes (the other is BRCA1) that have been identified as increasing breast cancer risk. These two genes also increase a woman's risk for developing ovarian cancer.

Because mutated genes can be passed down through the father as well as the mother, you are at the same increased risk for breast cancer as a woman whose mother had breast cancer and had the BRCA2 gene would be.

It is usually recommended to have someone who already has cancer tested to see whether she (or he) has one of the BRCA genes before testing other family members who may be at risk. You should find out if your father's sister has been tested to see if she carries the BRCA2 gene, and if she hasn't, if she would be tested.

You may also want to make an appointment with a genetic counselor in a program specifically for women at high risk for breast cancer. This would help you assess your breast cancer risk and determine if you want to be tested for BRCA2 yourself.

Does a woman's risk for breast cancer increase if her mother had simultaneous bilateral breast cancer?

Yes. A woman's risk of developing breast cancer is higher than that of the average woman if her mother had simultaneous bilateral breast cancer.

Because of your mother's experience, it is recommended that you be seen by a breast specialist or at a clinic for high-risk women. You could also make an appointment with a genetic counselor. In either of these settings you would be seeing a specialist who could use a computer program like BRCAPRO to assess your risk for developing breast cancer. The computer program takes into account your age, your mother's experience, and other personal risk factors to assess risk. (The most widely used model for assessing risk, the Gail model, does not take into account a mother's bilateral breast cancer. That is why you would need to see a specialist familiar with a risk predictor like BRCAPRO.)

My mother took DES. Does that increase my risk for developing breast cancer?

DES (diethylstilbestrol) was used between the 1940s and 1960s to increase fertility and prevent miscarriage. Not only was it ineffective, but it had health consequences for the women who used it, and for their children.

Studies have shown that the daughters of the women who took DES are at increased risk of developing cancer of the vagina or cervix. One study found that daughters may also have a slightly higher risk of developing breast cancer after age 40. But although their risk was higher, the actual number of cancers that developed was low. Specifically, the study showed that for every 1000 women between the ages of 45-49 who had been exposed to DES in utero, four new cases of breast cancer per year would be expected to develop while two new cases per year would be expected to develop in 1000 women who had not been exposed to DES.

Since then, a 2010 study published by a European research group in Cancer Causes and Control found no difference in breast cancer risk between DES daughters and unexposed women. However, a 2011 study published in October 2011 in the New England Journal of Medicine that compared 4,600 women who had been exposed to DES in utero with 1,900 women who had not, found that in women 40 years of age or older the cumulative breast cancer risk was 3.9% for those who had been exposed compared with 2.2% for those who had not—making the risk about two percent higher in the DES daughters.

More Information:

- CDC DES Update Campaign Provides information about DES exposure.

- DES Cancer Network A resource for DES-exposed women and their families.

- NIH—DES: Questions and Answers Answers common questions about DES.

- DES Action A resource for DES-exposed mothers, daughters, and sons who may need special health care.

Is it true that I have a one-in-eight chance of getting breast cancer?

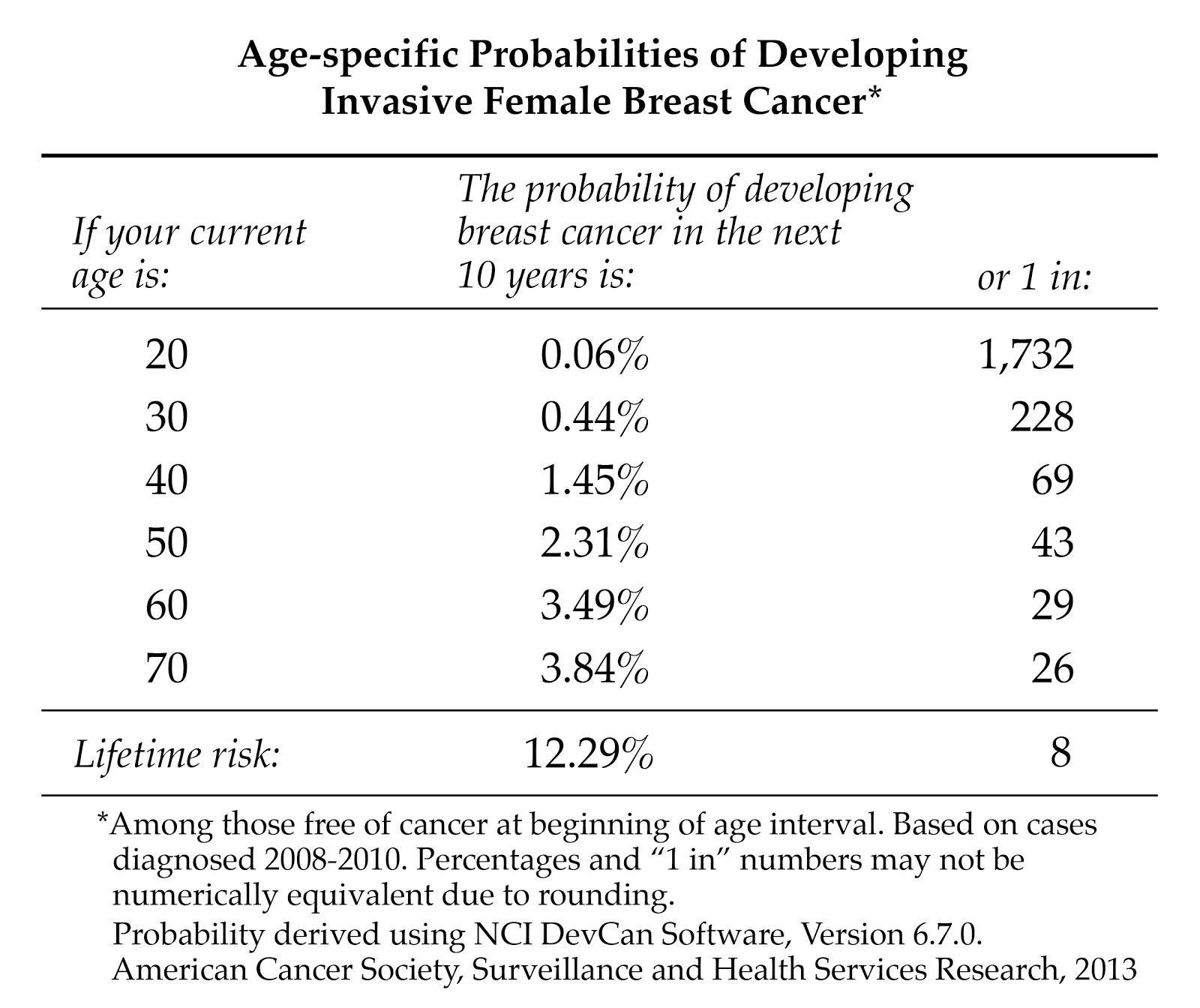

The one in eight statistic doesn't accurately reflect breast cancer risk. Age is the most important risk factor for breast cancer. That means the older a woman is, the greater her risk of developing the disease. Statistics from the US National Cancer Institute show that a woman's chance of being diagnosed with breast cancer by age is:

"Ever" means that you have a one in eight chance of getting breast cancer after the age of 70 if you don't die of anything else first. It's understandable why many women fear breast cancer as they grow older. But the reality is that most women over 70 will die of heart disease, not breast cancer.

To learn more about these risk statistics, you can read the National Cancer Institute's Fact Sheet Probability of Breast Cancer in American Women.