One of the most remarkable things about the breast is it is the only organ you are not born with. You are born with a nipple and lots of potential: stemcells behind the nipple that have the capacity of becoming breast ducts given the right hormonal stimulation.

When you add the hormones of puberty your nipple grows and then behind it a whole organ forms. When a woman becomes pregnant the hormones take the breast tissue to the next level, ready to turn blood into milk to feed the child. Not only does the breast milk nourish the child, it also passes on some of the mother’s immunity to the local environment as well as important bacteria and viruses needed to colonize the child’s gut. Once its job is over, the breast then cleans up all the milk making cells and ducts, and makes new ones so it will be ready for the next child. Finally, when a woman enters menopause it goes into retirement.

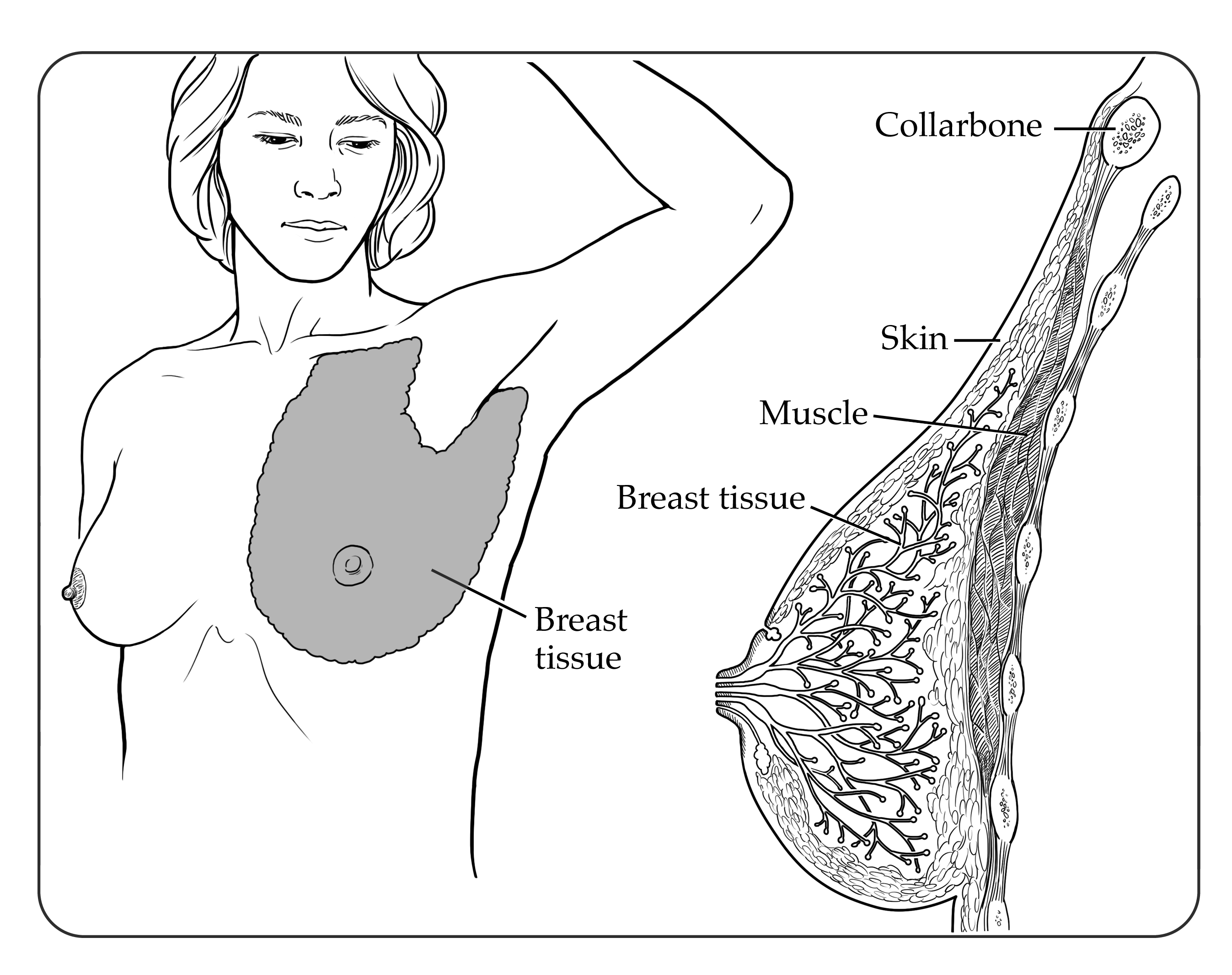

The breast itself is usually tear-shaped. There’s breast tissue from the collarbone all the way down to the last few ribs, and from the breastbone in the middle of the chest to the back of the armpit.

Often there’s a ridge of fat at the bottom of the breast—the inframammary ridge. This ridge is perfectly normal, and is the result of the fact that we walk upright and our breasts fold over themselves. The areola is the darker area of the breast surrounding the nipple. Its size and shape vary from woman to woman, and its color varies according to complexion. In most women, it gets darker after the first pregnancy. There are hair follicles around the nipple, so most women have at least some nipple hair. You may also notice little bumps around the areola that look like goose pimples. These are the little glands known as Montgomery’s glands, which sit just below your areola and provide lubrication during breastfeeding.

Sometimes nipples are “shy”: when they’re stimulated they retreat into themselves and become temporarily inverted. This is nothing to worry about; it has no effect on milk supply, breastfeeding, sexual pleasure, or anything else.

Inside, the breast tissue is sandwiched between layers of fat; behind that is the chest muscle. The fat has some give to it, which is why breasts bounce. The breast tissue is firm and rubbery. The breast also has its share of the connective tissue that holds the entire body together. This material creates a solid structure—like gelatin—in which the other kinds of tissues are loosely set. This is sometimes called the stroma and is getting more attention as recent studies show its importance in breast cancer.

Like the rest of the body, the breast has arteries, veins, and nerves. There is another, almost parallel, network of vessels called the lymphatic system (or lymphatics) which works like recyclers or filters for helping the body fight infection. The job of this network is to collect the debris from the cells and strain it through the lymph nodes found scattered in nests throughout the body; they then send the filtered fluid back into the bloodstream to be reused.